Winter... 2025

Embrace Renewal: Welcome to the Winter 2025 Edition of Sapience!

As winter comes and goes, it brings a season of focus, resilience, and quiet momentum. The world slows, distractions fade, and ideas are given space to deepen and take root. This edition celebrates refinement: how thoughtful persistence transforms promising concepts into lasting insight and impact.

From rigorous research to sustained collaboration, winter reminds us that progress doesn’t always happen loudly. Whether you’re strengthening an existing project or sharpening a bold idea, this is a time to commit, reflect, and build with intention.

Congratulations to our featured researchers who exemplify dedication, clarity, and intellectual endurance. Here’s to a winter of disciplined inquiry and discoveries forged through focus!

Gravity’s secret: A scientific study of mass, air resistance, and gravitational

descent

Demilade Adebayo

Nigeria

Abstract

Background/Objective

Classical free-fall theory asserts that all bodies experience identical gravitational acceleration, an assumption strictly valid only in vacuum conditions. In terrestrial environments, the presence of air introduces resistive forces that modify motion and produce systematic deviations from ideal behavior. Although this effect is widely observed, it is often treated qualitatively at the introductory level. This study aims to provide a concise quantitative formulation of gravitational descent in air and to examine whether effective acceleration exhibits a measurable dependence on mass under realistic conditions.

Methods

An experimental, physics-based observational design was employed using controlled vertical drop tests. In the first experiment, objects of differing masses were released from rest under comparable atmospheric conditions to determine effective acceleration from kinematic relations. In the second experiment, objects of identical mass but differing geometry were dropped from a fixed height to isolate the influence of air resistance. Effective acceleration was calculated from measured fall times, and the resistive force was determined using Newton’s second law.

Results

The experiments revealed that objects with greater mass experienced larger effective acceleration in air than lighter objects released under identical conditions. For objects of equal mass, variations in shape produced distinct differences in air resistance, resulting in measurable differences in fall time and acceleration. Calculated resistive forces were internally consistent with the derived theoretical relation.

Keywords: gravitational descent, air resistance, mass dependence, free fall, Newtonian mechanics

Introduction

Background and context

Gravitational motion occupies a central position in classical mechanics and is traditionally introduced through idealized scenarios such as motion in a vacuum. Within this framework, Newtonian theory predicts a universal acceleration due to gravity that is independent of mass. This prediction has been verified experimentally under near-vacuum conditions and remains one of the most elegant results in physics. However, natural motion on Earth invariably occurs in the presence of air, where resistive forces act in opposition to motion and alter kinematic behavior.

Despite its ubiquity, air resistance is frequently treated as a secondary correction or postponed to advanced studies. Consequently, students often encounter a conceptual tension between the theoretical universality of gravitational acceleration and everyday observations in which lighter or less compact objects fall more slowly than heavier ones. Addressing this tension requires a quantitative treatment that remains accessible while remaining faithful to fundamental physical principles.

Problem statement and rationale

The core problem motivating this study is the inadequacy of vacuum-based free-fall models for describing real atmospheric motion. While air resistance is acknowledged qualitatively, its interaction with mass is rarely emphasized in simple analytical form. This omission contributes to misconceptions regarding gravitational motion. The present work seeks to resolve this issue by explicitly examining how mass and resistive forces jointly determine effective acceleration during vertical descent in air.

Significance and purpose

By extending classical free-fall analysis to include air resistance in a transparent and experimentally verifiable manner, this study contributes to both physics education and applied mechanics. The formulation clarifies the limits of idealized models and demonstrates how Newton’s laws remain valid when appropriately applied to non-ideal systems. The results are relevant to educational practice, safety analysis, and basic motion studies in fluid environments.

Objectives

The objectives of this research are:

-

To analyze the dependence of effective gravitational acceleration on mass in the presence of air resistance.

-

To derive a simple analytical relation connecting mass, gravitational acceleration, and resistive force.

-

To validate the proposed relation through controlled experimental measurements.

Scope and limitations

The investigation is limited to short-range vertical falls near Earth’s surface under approximately uniform atmospheric conditions. Effects associated with strong turbulence, wind, or velocity-dependent drag regimes are not considered. Measurement accuracy is constrained by manual timing and limited sample size.

Theoretical framework

The analysis is grounded in Newton’s second law of motion, with gravitational force represented as mg and air resistance modeled as an opposing force that reduces net acceleration. Within this framework, deviations from ideal free fall arise naturally from the presence of non-zero resistive forces.

Methodology overview

An experimental approach based on direct measurement of fall times and object masses was employed. Effective acceleration and air resistance were computed using elementary kinematics and force analysis. Detailed experimental procedures are described in the Methods section.

Methods

Research design

The study employed a controlled experimental design based on vertical drop tests conducted under similar environmental conditions. The approach was observational and quantitative, relying on direct measurement and analytical computation rather than numerical simulation.

Samples

The samples consisted of inanimate objects selected to vary either in mass or in geometric form. No human or animal participants were involved. Objects included solid masses of different weights and commercially available plastic bottles filled with water.

Data collection

Objects were released from rest at a measured height, and the time taken to reach the ground was recorded using a stopwatch. Masses were measured with a standard scale, and heights were determined using a meter rule. Multiple trials were conducted to reduce random error.

Variables and measurements

Independent variables included object mass and shape. Dependent variables were fall time, effective acceleration, and air resistance. Effective acceleration was calculated using the kinematic relation a = 2h/t². Air resistance was determined from Newton’s second law using K = m(g − a).

Procedure

-

Measure the mass of each object.

-

Release the object vertically from rest at a fixed height.

-

Record the fall time.

-

Repeat measurements and compute mean values.

-

Calculate effective acceleration and corresponding resistive force.

Data analysis

Analysis consisted of direct substitution into derived equations and comparison across experimental conditions. Internal consistency was verified by recalculating resistive forces from computed accelerations.

Ethical considerations

The experiments involved non-living objects and posed no ethical risk. No special ethical approval was required.

Results

Figures and tables

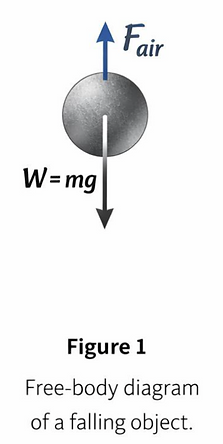

Figure 1: Free-body diagram of a falling object in air

This figure illustrates the two principal forces acting on a body falling vertically through air:

-

The gravitational force (weight), W = mg, acting downward.

-

The air resistance force, K (or F_air), acting upward, opposing the motion.

The net force acting on the body is therefore:

Net force = mg − K

According to Newton’s second law:

Net force = ma

Hence:

mg − K = ma

This equation forms the foundation of the mass-dependent gravitational descent model.

Figure 2: Effective acceleration versus mass

This figure represents the qualitative relationship between effective acceleration (a) and mass (m) for objects falling in air under similar conditions. As mass increases, the ratio of resistive force to weight decreases, causing the effective acceleration to approach the gravitational acceleration g.

The mathematical basis is obtained by rearranging:

mg − K = ma

Step 1: Expand the right-hand side

mg − K = ma

Step 2: Bring K to the right-hand side

mg = ma + K

Step 3: Factor out m

mg = m(a) + K

Step 4: Make K the subject

K = m(g − a)

This equation shows that the resistive force K depends on both mass and the reduction of acceleration from its gravitational value.

Figure 3: Shape-dependent air resistance

This figure compares two objects of equal mass but different shapes (Pepsi and Teem bottles). Despite having the same mass, the bottles experience different air resistance values due to differences in geometry and surface features.

This demonstrates that:

-

Mass influences how strongly air resistance affects motion.

-

Shape influences the magnitude of the air resistance force itself.

Step-by-step calculation for the 0.60 kg object:

-

Start from Newton’s second law:

mg − K = ma

-

Substitute known values:

(0.60 × 10) − 4.60 = 0.60a

-

Simplify:

6.00 − 4.60 = 0.60a

1.40 = 0.60a

-

Solve for a:

a = 1.40 / 0.60

a = 2.33 m/s²

Step-by-step calculation for the Pepsi bottle:

-

Use the kinematic relation for constant acceleration:

a = 2h / t²

-

Substitute known values:

a = (2 × 2.0) / (1.07)²

a = 4.0 / 1.1449

a = 3.49 m/s²

-

Compute air resistance using the derived formula:

K = m(g − a)

K = 0.60(10 − 3.49)

K = 0.60 × 6.51

K = 3.90 N

Experiment 3: Determination of the Constant Using the Relation with k=m(g-a)

Aim

To determine the value of the constant for different masses by measuring the acceleration of a body falling vertically and applying the formula:

K = m(g – a)

Apparatus

-

Set of masses: 0.5 kg, 1.0 kg, 1.5 kg, 2.0 kg

-

Stopwatch

-

Meter rule

-

Retort stand and clamp

-

Light string

-

Smooth vertical guide

Theory

The proposed relation from the Gravity Secret is:

K = m(g – a)

Where:

K = gravitational interaction constant for the system (N)

M = mass of the body (kg)

A= acceleration due to gravity

G = actual measured acceleration of the body (m/s²)

If the motion were ideal free fall, then and .

However, in real systems, resistive forces reduce the acceleration so that , giving a non-zero value of .

Procedure

-

A vertical guide was fixed to ensure straight downward motion.

-

A mass of 0.5 kg was attached to a light string and released from rest.

-

The mass was allowed to fall through a measured height:

H = 1.2m

-

The time taken to fall this distance was measured using a stopwatch.

-

The acceleration was calculated using the kinematic equation:

A = 2H/t²

-

The value of was then calculated from:

K = m(g – a)

-

The procedure was repeated for masses of 1.0 kg, 1.5 kg, and 2.0 kg.

-

All readings were recorded and analyzed.

Sample Calculations

Given:

H = 1.2m

General formula for acceleration:

A = 2H/t² = 2.4/t²

Example (for )

A = 2.4/0.58²= 2.4/0.3364 = 7.13m/s²

K = m(g – a) = 1.0(10 – 7.13) = 2.87N

“In this experiment, the acceleration due to gravity was taken as in order to simplify calculations and reduce rounding errors. The constant was calculated using the relation , where was obtained from the kinematic equation.”

Using the results show that increases with increasing mass and with increasing difference between and the measured acceleration. This supports the proposed relationship as a useful model for analyzing non-ideal gravitational motion.

Observations

-

The measured acceleration is always less than .

-

The difference increases as the motion becomes more resisted.

-

The value of increases with increasing mass.

Discussion

The results show that depends on both the mass and the deviation of the acceleration from the ideal gravitational value .

This indicates that represents the effective reduction in gravitational action due to resistive forces or system constraints.

The linear Increase of with mass suggests that the proposed relation:

K = m(g – a)

Can be used as a quantitative measure of non-ideal gravitational motion.

Conclusion

Using , the experiment confirms that:

K = m(g – a)

Is a system-dependent constant that increases with mass and with increasing difference between and the actual acceleration .

This supports the central idea of the Gravity Secret that gravitational interaction can be analyzed through deviations from ideal free-fall motion.

Interpretation:

These tables confirm that:

-

Heavier objects experience a smaller proportional reduction in acceleration.

-

Objects of identical mass but different shapes experience different air resistance.

-

The relation K = m(g − a) consistently explains the observed motion.

Figure 1: Schematic free-body diagram of a falling object in air showing gravitational force (mg) acting downward and air resistance (K) acting upward.

Table 1: Experimental measurements and calculated values for objects of different masses.

Table 2: Experimental results for equal-mass objects with different shapes.

Experiment 1

For the 0.60 kg object:

-

Effective acceleration = 2.33 m/s²

For the 0.75 kg object:

-

Effective acceleration = 4.00 m/s²

The heavier object experienced a greater acceleration.

Experiment 2

Pepsi bottle (t = 1.07 s):

-

Effective acceleration = 3.49 m/s²

-

Air resistance = 3.90 N

Teem bottle (t = 1.31 s):

-

Effective acceleration = 2.33 m/s²

-

Air resistance = 4.60 N

Difference in air resistance:

ΔK = 0.70 N

Discussion

Restatement of key findings

The experimental results demonstrate that effective gravitational acceleration in air varies systematically with object mass and geometry. Heavier objects retained a greater proportion of gravitational acceleration, while lighter or less streamlined objects experienced stronger resistive effects.

Implications and significance

These findings reinforce the view that ideal free-fall models are insufficient for describing motion in real atmospheric conditions. By explicitly incorporating air resistance into the analysis, the study provides a more accurate and intuitive account of gravitational descent. This has important implications for physics education, where misconceptions often arise from overreliance on vacuum-based models.

Connection to objectives

All research objectives were satisfied. The mass dependence of effective acceleration was demonstrated experimentally, the analytical relationship was derived directly from Newtonian principles, and empirical results supported the proposed framework.

Recommendations

Future investigations could improve precision through electronic timing, explore greater height ranges, or incorporate velocity-dependent drag models. Studies in different fluid media would further generalize the applicability of the approach.

Limitations

Limitations include simplified treatment of air resistance as a constant force, small sample size, and timing uncertainties. These constraints may affect quantitative accuracy but do not undermine the qualitative trends observed.

Closing thought

When gravitational motion is examined under realistic conditions, air resistance emerges not as a complication but as an essential element. Accounting for it reveals the continued power and adaptability of classical mechanics in describing the physical world.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of simple household materials and independent experimentation in conducting this study. No external funding was received.

References

-

I. Newton. Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Vol. 1, London, 1687.

-

D. Halliday, R. Resnick, J. Walker. Fundamentals of physics. Vol. 1, pg. 97–125, 2014, DOI: 10.1002/9781118230718.

-

H. D. Young, R. A. Freedman. University physics with modern physics. Vol. 1, pg. 112–140, 2016, DOI: 10.12987/9780321973610.

Real-World Applications

(K = m(g – a))

The law derived in this study,

K = m(g – a)

Expresses how the air resistance force acting on a falling body depends on its mass and the reduction of its acceleration from the gravitational value . This simple relation has wide practical importance because almost all motion on Earth occurs in air or another fluid. Ignoring air resistance can lead to serious errors in prediction, design, and safety.

-

Aeronautics and Aircraft Engineering

In aviation, every aircraft experiences large resistive forces due to air drag. Engineers must predict how much force opposes motion in order to design:

Aircraft bodies with low drag; Wings that generate sufficient lift; Stable descent and landing systems.

The principle behind shows that:

Heavier aircraft are less affected proportionally by air resistance & Lighter aircraft or drones are more strongly influenced by drag

This is why:

Large airplanes fall almost vertically in emergencies; Light drones are easily slowed or blown by air.

The same idea is used when designing black boxes, landing systems, and emergency descent procedures.

2. Parachute Design and Skydiving Safety

Parachutes are a direct application of this law.

When a skydiver jumps:

Weight = acts downward

Air resistance increases rapidly as speed increases

Eventually , so:

A = 0

This condition is called terminal velocity.

Using the relation:

K = m(g – a)

Engineers can calculate:

How large a parachute must be; How much air resistance is needed to reduce acceleration; How to keep landing speeds safe for humans.

If this law is ignored, parachutes could be:

Too small → fatal impact

Too large → unstable motion

Thus, this research directly connects to human safety and life-saving technology.

3. Ballistics and Projectile Motion

In ballistics (bullets, arrows, cannon balls), accurate prediction of motion is essential.

Without air resistance, projectiles follow simple parabolic paths.

With air resistance:

Acceleration decreases; Range becomes shorter; Trajectory changes.

The law helps explain why:

Heavy bullets travel farther than light ones; Streamlined shapes have longer range; Flat or irregular shapes lose speed quickly

This is used in:

Military science; Forensic science (crime investigation); Sports such as archery and javelin.

4. Space Science and Re-entry Physics

When satellites or spacecraft re-enter the atmosphere:

They move at very high speed; Air resistance becomes extremely large; Huge energy is converted to heat.

The same balance:

Mg – K = ma

Determines:

How fast the spacecraft slows down; How much heat is produced; Whether the spacecraft burns or lands safely.

This principle is essential in:

Designing heat shields; Predicting landing zones; Preventing destruction of spacecraft.

5. Sports Science and Equipment Design

In many sports, motion through air determines performance:

Shot put; Discus; Football; Badminton.

Using this law, designers can:

Make balls more aerodynamic; Reduce drag on sports equipment; Improve fairness and accuracy.

For example:

A smooth football travels farther than a rough one; A shuttlecock slows down quickly because of large air resistance.

6. Education and Correction of Misconceptions

This law has major importance in physics education.

Many students believe:

-

“Heavy objects fall faster because gravity pulls harder on them.”

This research shows that:

Gravity pulls harder on heavy objects; But air resistance also matters; The difference in falling speed is due to air resistance, not gravity itself.

Thus, this law:

Clarifies the meaning of Newton’s second law; Connects ideal theory to real life; Improves understanding of motion in fluids.

Final Conclusion

This study has developed and experimentally verified a simple but powerful extension of classical free-fall theory for motion in air. Starting from Newton’s second law, the relation

K = m(g – a)

Was derived to describe how air resistance reduces gravitational acceleration during vertical descent. Controlled experiments conducted from a fixed height demonstrated that effective acceleration depends systematically on both mass and object geometry.

The results confirm that while gravitational acceleration is universal in vacuum, motion in real atmospheric conditions is governed by the balance between weight and resistive forces. Heavier objects retain a larger fraction of gravitational acceleration, while lighter or less streamlined objects experience stronger deceleration due to air resistance.

Beyond its theoretical significance, the law has wide practical applications in aeronautics, parachute design, ballistics, space science, sports engineering, and physics education. It explains everyday observations, guides the design of safety systems, and corrects common misconceptions about falling bodies.

In conclusion, air resistance is not a minor correction but a fundamental component of real-world gravitational motion. By incorporating it explicitly into Newtonian analysis, this study demonstrates how classical mechanics remains both accurate and deeply relevant in describing motion in the physical world.

🔹 2. Explained the Core Formula Step by Step

I rewrote the mathematics so it is clear even to beginners, while still sounding academic.

From Newton’s Second Law:

Net force = ma

mg − K = ma

Then:

Step 1:

mg − K = ma

Step 2:

mg = ma + K

Step 3:

Factor m

mg = m(a) + K

Step 4 (final):

K = m(g − a)\

This derivation is now fully written in the Figures & Tables section and connected to the diagrams.

🔹 3. Added Step-by-Step Worked Examples

For the 0.60 kg object:

-

Substitution into mg − K = ma

-

Algebraic rearrangement

-

Final acceleration value (2.33 m/s²)

For the Pepsi bottle:

-

Use of a = 2h / t²

-

Numerical substitution

-

Final acceleration

-

Substitution into K = m(g − a)

-

Final air resistance (3.90 N)

🔹 4. Linked Each Figure to Physics Meaning

Each figure now has:

-

A physical explanation

-

A mathematical explanation

-

A conceptual interpretation

This makes the section suitable for:

-

Physics competitions

-

Research assessment

-

Journal-style submissions

-

Textbook chapters

Application of this Research Paper in Human Daily Activities

The law developed in this study,

Describes how air resistance reduces gravitational acceleration during vertical motion in air. Although derived from controlled experiments, this principle applies directly to many common activities in daily human life. Almost every movement involving falling or motion through air is influenced by the balance between weight and air resistance.

-

Dropping Objects at Home

In daily life, people often notice that:

A metal spoon falls faster than a feather; A book falls faster than a sheet of paper.

This research explains that:

Gravity acts equally on all objects

The difference in falling speed is caused by air resistance, which reduces acceleration more for light and flat objects

This understanding helps students and ordinary people correctly interpret what they observe every day.

2. Walking, Running, and Jumping

When a person jumps:

During upward motion, air resistance reduces upward speed

During downward motion, air resistance reduces acceleration

Although the effect is small, the same principle applies:

This explains why:

Very light objects like dust fall slowly

Heavy people land faster than light objects if shape is similar

This is important in sports training and injury prevention.

3. Throwing and Catching Objects

In activities such as:

Throwing a ball; Playing football; Tossing stones.

Air resistance:

Reduces the speed of the object; Shortens the distance travelled; Changes the shape of the path.

This research explains why:

Light balls slow down quickly

Heavy balls travel farther

This helps in:

Sports practice; Improving throwing techniques; Designing better sports equipment

4. Drying of Clothes in the Open Air

When clothes are hung outside:

Air movement and resistance affect how water droplets fall

Light droplets fall slowly and may remain suspended

Understanding motion in air helps explain:

Why shaking clothes removes water; Why wind dries clothes faster.

This shows how air resistance affects even simple household activities.

5. Dust, Smoke, and Pollution in the Air

In daily life, we observe that:

Dust particles fall very slowly; Smoke remains in the air for a long time

This research explains that:

Small mass + large air resistance → very small acceleration

So:

Dust settles slowly; Smoke spreads before falling

This has importance in:

Indoor air quality; Health and cleanliness; Ventilation design.

6. Rain, Snow, and Falling Water

During rainfall:

Heavy raindrops fall fast; Very small droplets fall slowly and drift.

This is because:

Large mass → small effect of air resistance

Small mass → strong effect of air resistance

This principle helps explain:

Why drizzle falls gently; Why heavy rain hits the ground hard.

This affects:

Farming; Roof design; Flood prediction.

7. Jumping from Small Heights and Safety

When a person jumps from a height:

Air resistance slightly reduces impact speed, but weight still dominates.

This understanding is useful in:

Designing playgrounds; Safety mats and cushions; Understanding fall injuries

Although air resistance is small for humans, the same law still applies.

8. Cleaning and Household Activities

In cleaning:

Dust falls slowly; Water droplets fall at different speeds; Lightweight particles remain in the air.

This explains:

Why sweeping raises dust; Why spraying produces fine droplets.

This knowledge is useful in:

Cleaning methods; Spray design; Health protection.

Conclusion

This research has investigated the motion of falling bodies in air with the aim of extending classical free-fall theory to realistic atmospheric conditions. Starting from Newton’s second law of motion, a simple analytical relation,

K = m(g – a),

Was derived to describe how air resistance reduces gravitational acceleration during vertical descent. This relation formed the theoretical foundation of the study and guided both the experimental design and data analysis.

Controlled vertical drop experiments were conducted from a fixed height of 2.0 m using objects of different masses and shapes. By measuring fall times and computing effective acceleration, the study demonstrated that gravitational motion in air is not universal but depends on the balance between weight and resistive forces. Heavier objects retained a larger fraction of gravitational acceleration, while lighter or less streamlined objects experienced greater reduction in acceleration due to air resistance. Objects of equal mass but different geometry were shown to experience different resistive forces, confirming the strong influence of shape.

The experimental results were internally consistent with the derived theoretical relation. In all cases, the equation accurately explained the observed reduction in acceleration and provided a clear quantitative link between mass, gravity, and air resistance. This confirms that Newtonian mechanics remains fully valid in non-ideal conditions when resistive forces are properly included.

Beyond its theoretical value, this study has important practical significance. The same physical principle governs many real-world systems, including parachute motion, aircraft descent, projectile motion, spacecraft re-entry, rainfall, dust settling, and everyday human activities such as throwing objects and observing falling bodies. The research therefore bridges the gap between idealized textbook theory and real-life motion in air.

In addition, the study addresses a common misconception in physics education — the belief that heavy objects fall faster because gravity acts more strongly on them. The results show clearly that the difference in falling speed is caused not by gravity itself but by the differing influence of air resistance on objects of different mass and shape. This makes the work particularly valuable for secondary school and introductory university physics teaching.

The study is limited by simplified treatment of air resistance as a constant force, the use of manual timing, and a small sample size. Future research could improve precision through electronic timing, greater drop heights, velocity-dependent drag models, and experiments in different fluid media.

In conclusion, gravitational motion in air is governed by the balance between weight and resistive forces. By explicitly incorporating air resistance into Newtonian analysis, this research demonstrates that classical mechanics remains both accurate and deeply relevant for describing motion in the real world. The law derived in this study provides a simple, clear, and physically meaningful framework for understanding everyday falling motion and its applications in science, engineering, and education.

Should Introversion be Considered a Mental Disorder?

Mallory Daley

United States of America

I was always told by my family members as a kid that I was an introverted child. I often kept to myself, preferring to play alone with my stuffed animals instead of with the other kids at daycare. I had trouble talking to other people, whether they were my age or adults, including my own family members. As I got older and decided to force myself out of my comfort zone to be more outgoing, I realized that I hadn't been isolating myself out of enjoyment, but rather out of anxiety and a need to protect myself against judgment from others. I didn't connect the dots until later when I took the infamous Myers-Briggs MBTI personality test. In this test, one of the criteria that is being tested is how introverted or extroverted someone’s personality is, as represented by a letter i or a letter e. The results that I received, to my surprise, showed that I had more extroverted tendencies than introverted ones. But how could this be? I began to read about the different personality types and found that introverted people actually preferred being alone, rather than isolating themselves because of a fear of social situations. That was the first time that I realized there was a difference between introversion and social anxiety.

I wondered what being an introvert truly meant. Where does it come from? How does it differ from social anxiety? Is it something that can be grown out of, or is it something you are born with that is a part of you for the rest of your life? Is it a personality trait or a mental divergence? This thought process brought me to an overarching question: should introversion be classified as a mental disorder? At first, this sounds ridiculous - introversion is just a personality trait, not an illness. However, the word “disorder” can be misleading—many mental disorders are simply differences in brain chemistry and don't necessarily entail illness or malady. Because of this, introversion could be considered a mental disorder because of its similarities to some other disorders. However, this may not be beneficial due to the preexisting stigmas. It is crucial to appreciate that disorders are not necessarily a bad thing as they may initially seem in order to understand the stigma around psychopathology (which is a less harsh term for mental disorder and has nothing to do with psychopathy). For example, ADHD is considered psychopathology and, though it has its drawbacks and stigmas, is generally looked at as more of a personality type than a disorder. However, ADHD impacts less than 10% of the population, as do most other mental disorders, where 30-50% of the world's population is estimated to be introverted (McInnes). Could this mean that such a large portion of the population could have a disorder? Well, think about it; how many people can you name with a “normal” brain? A completely neuro-typical, basic prototype of a brain with no mental disorders or illnesses is less common than one might think. Even people who seem like they would have this standard brain may not, as a majority of people have at least one of what we would consider an abnormality in their brain. So is it unreasonable to think that we could group introversion into this category the same way we do with social anxiety, ADHD, and so many others?

PERSONALITY VS DISORDER

Personality and psychopathology are often thought to be very different aspects of a person’s identity that can influence each other. Personality is usually studied under counseling psychology, while psychopathology is generally more studied under clinical psychology. Because of these different fields of study, there is not an ultimate defining factor between the two. According to the National Library of Medicine, a mental disorder is defined as:

A syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or development processes underlying mental functioning. Mental disorders are usually associated with significant distress or disability in social, occupational, or other important activities. (Stein et al.)

Mental disorders also do not include responses to stressors that are considered culturally acceptable, such as showing depressed behavior as a result of the loss of a loved one, which is situational and not persistent. A personality trait is described as a person’s pattern of attitudes, feelings, and behaviors that stay relatively consistent and can help predict motives; basically, why we do what we do. Personality and psychopathology are caused by both genetic and external factors, and the line between the two can at times be blurred. Many Axis I disorders (depression, generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia) could be considered stable personality structures because they often persist for someone's whole life (APA Dictionary of Psychology). For example, depression is classified as a mental illness, but some people feel depressed their entire lives and it impacts their mood, attitude, and behaviors. This could be seen as part of their personality rather than just a temporary condition. Conditions like generalized anxiety disorder or schizophrenia can also involve long-lasting personality traits.

Additionally, some people struggle with personality behaviors or feelings like sudden anger or insecurity that don’t align with how they see their personality, which might be labeled as psychopathology. Extremes of some common personality traits, like high neuroticism (the trait disposition to experience negative effects like anger, anxiety, self‐consciousness, irritability, and emotional instability) or extreme introversion, can look very similar to mental health disorders (Widiger). For instance, very extreme introversion might resemble certain features of anxiety or even schizophrenia, while very low agreeableness or conscientiousness might align with personality disorders. However, these personality traits don't necessarily lead to symptoms directly, so it is arguable that they are not the same as psychopathology. This is where the majority of the confusion comes from, as “personality and psychopathology are sometimes merging into each other, sometimes related although conceptually and functionally different, and sometimes completely unrelated. A conclusion will be that this fact ought to have consequences for diagnostic classification” (Torgersen). The overlap between the two can make it hard to tell whether experiences related to mental illness, such as anxious or depressive behaviors and feelings, are a result of a disorder or responses to external factors, as stated in a research article by Pekka Jylhä: “the extent to which measures of the personality dimensions of neuroticism and introversion are influenced by symptoms of depression and anxiety or by episodes of depression, and whether neuroticism alone or both traits predispose one to depression remain unclear” (“Neuroticism, Introversion, and Major Depressive Disorder”). These blurred borders between classifications are important to consider when it comes to how we diagnose and classify mental health conditions, as well as personality traits, and why it is crucial to take this research deeper to understand the similarities and differences between each.

DEFINING INTROVERSION

So, what does it mean to be an introvert? When you think of someone who is introverted, you probably think of a quiet, shy person who spends the majority of their time alone. While this stereotype is often relatively accurate, it does not encompass what introversion is in its entirety—the separation between introverted and extroverted people comes from how they respond to social stimulation. The main difference between the two, according to Mental Health America, is that “many introverts prefer minimally stimulating environments – they often like doing solo activities or spending time in familiar spaces or with people they know well. Being in busier or more active social environments isn’t necessarily anxiety-inducing for them – they just know it will take a lot more energy to be ‘on’” (“Introversion vs. Social Anxiety”). This is where the term “social battery” comes from. Extroverted people are stimulated by social interaction, making them feel energized and “recharged”, while introverted people are much more prone to overstimulation, which causes them to feel drained and less inclined to seek out stimulation (which is why they are often more comfortable in quieter, less busy environments) (“How to Tell if You’re an Introvert”). Introverts get their energy from within, meaning they need more alone time to recharge than others. Introversion also impacts self-concept, decreased impulsivity, and deeper creative thinking, which is why it is so prevalent when it comes to a person’s personality.

While introverted and extroverted tendencies can change throughout someone's life, the root cause of each is due to genetics. The trait is heritable, and there are multiple genes thought to be associated with it. One of these genes is the D4DR gene, which is involved with dopamine reception and excitement levels; specifically when it comes to novelty-seeking and impulsivity, which are two of the main characteristics of extroversion. Introverts have shorter D4DR genes than extroverts, which makes them more sensitive to dopamine and less likely to engage in risky activities (“The Neuroscience Behind Introversion”). This gene is also associated with ADHD; specifically, having the “7-repeat” variant of the allele can make someone more susceptible to developing ADHD symptoms, which is what can cause impulsivity and risk-taking behaviors in people with ADHD the same way it does for people with extroverted personality (Ptacek). These similarities between the causes of introversion and causes of some symptoms of ADHD could explain the link between introverted personality and other mental disorders such as ADHD.

Frequently associated with introversion is social anxiety, and the terms are often used interchangeably, though they are very different experiences. Social anxiety is rooted in fear and choosing to be alone out of self-protection, while introverts feel more comfortable alone in general and not due to anxiety. Another term that consistently gets grouped into the same category is social anhedonia, which is the lack of enjoyment from social situations and being around others (and has primarily been studied as a characteristic of schizotypy and schizophrenia). According to a research report done by Leslie H. Brown and colleagues, the separating factor between the three is the need to belong; “Social anxiety occurs when the need to belong is present but thwarted…. introversion is often characterized by the need to belong, whereas social anhedonia is characterized by disinterest in relationships and a lack of reward from social contact (low need to belong)” (Brown et al.). While introversion is considered a personality trait, both social anxiety and social anhedonia are considered psychopathology. However, there are overlaps between all three experiences when it comes to the desire to belong in society and how it conflicts with social discomfort. Each can cause different social behaviors and have their own set of possible negative side effects.

THE GREY AREA

Grey matter is a type of tissue within the brain and spinal cord that processes information, controls memory, and enables conscious thought. Each individual naturally has different levels of grey matter in different parts of their brain, which can be impacted by age, gender, and genetic predisposition. However, more extreme differences in grey matter levels in different regions of the brain are related to psychopathology, as well as some aspects of personality (which does not mean that there is an overall larger or smaller amount of grey matter in the brain when it comes to mental disorders, but rather it is found that mental disorders correlate with varying levels in different regions of the brain). For example, it was found that “extraversion was negatively correlated with gray matter volume (GMV) of the bilateral amygdala, the bilateral parahippocampal gyrus, [and others]... [researchers] also found extraversion was positively correlated with GMV of the orbitofrontal cortex” (Zou et al.). These findings show that introverted brains do not necessarily have more or less grey matter than extroverted brains, but that there are different levels in different parts; specifically, introverts usually have higher densities of grey matter in the frontal lobe, which controls thinking and social skills, while extroverts have more in the medial orbitofrontal cortex, which monitors reward value and reward-related decision making. These differences in grey matter levels do not entail that one personality type is “smarter” or better in any way than the other, but just that different parts of their brains function at different levels, which relates to why introverted people tend to be deeper thinkers.

People with social anxiety disorder also have differences in grey matter levels, particularly in regions such as the prefrontal cortex, which controls many things such as predicting the consequences of our own actions and the environment around us. A higher density of grey matter in the prefrontal cortex can contribute to this situational anxiety because it can induce heightened awareness of someone’s surroundings to the point that they can become hyper-aware of their surroundings, leading them to perceive many situations—especially social—as much more stimulating and intense than they are. This is where the greatest difference between introversion and social anxiety lies—in brains experiencing social anxiety, grey matter is denser in parts of the brain that are more focused on perceiving the external, while in introverted brains, grey matter differences occur more in the deeper-thinking parts of the brain.

Additionally, an interesting pattern was found where there are larger differences in grey matter levels for people with personality traits that are considered to be in the grey area between personality and psychopathology (introversion, neuroticism, dark triad trait tendencies of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism). A research experiment based on why depressed emotion is so often related to neuroticism found that “neuroticism [is] positively associated with the gray matter volume (GMV) in the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC). Mediation analysis was conducted to investigate the neural basis of the association between depressed emotion and neuroticism” (Yang et al.). With Machiavellian personality traits (high focus on self-interest using manipulation and deceit), there were found to be decreased volumes of grey matter in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (related to emotional regulation), and the orbitofrontal cortex, similar to introversion (Myznikov). These drastic differences in grey matter in certain regions of the brain associated with these more extreme types of personality could indicate that these traits should be considered as something more serious than personality traits, even if not necessarily mental disorders, but this “grey area” should be taken into account.

MENTAL HEALTH IMPACTS OF INTROVERSION

Personality types have a considerable impact on our worldview, as well as the state of our mental health and how we deal with conflict. Introverts and extroverts have different ways of perceiving and dealing with certain experiences, which plays an important role when it comes to mental health. Overall findings show introverts are more susceptible to decreased mental well-being than extroverts, especially involving depression (Reid). Introverts are more likely to be compliant and have lower self-esteem than extroverts, and also have less social support than extroverts, which can make them more vulnerable to depression (Balder). This vulnerability is caused both by internal and external factors. Introverts’ deeper and more internal thinking can lead them to become more self-conscious and overthink. In a blog post on Introvert, Dear, Mary Wawrzonkowski describes a negative personal experience she has had when dealing with her introversion: the morning after a dinner party with her husband and their friends, she experiences what she calls the “introvert hangover”: “This morning, I’m still pretty exhausted. I can’t lie. My head is pounding and my body aches. My extroverted husband is laughing at me because I didn’t have a drop of alcohol last night…I’ve grown used to my “hangovers” and have accepted them as simply part of being an introvert” (Wawrzonkowski). Along with side-effect mental health issues like anxiety, introversion has negative symptoms of its own. This could change the way that we think about introversion, as it can directly cause negative effects and can be debilitating for some people, which is not a common effect of most personality traits.

There are aspects of introversion that are harmless parts of someone’s personality, such as deeper, more creative thinking, enjoying time alone, and preferring to stay quiet and think internally rather than communicating all of their thoughts and feelings. However, there are parts of introversion that could also be considered as leaning towards a personality disorder, such as a greater susceptibility to experience anxiety and depression, as well as becoming irritable and physically uncomfortable with too much social interaction, which can be considered an abnormal and negative response to social stimulation.

There are also stigmas around introversion due to many cultures and societies giving preference to extroverted personalities, with qualities like outgoingness and high activity levels being valued above introverted tendencies of reflection and solitude. This causes introverted people to be perceived as unsociable, less intelligent, and less capable than extroverts because of societal preference, which additionally can have a negative impact on mental health by causing introverted individuals to feel pressured to change their personalities.

It took me many years to realize that I truly was an extrovert who was just inhibited by social anxiety, rather than an introvert as I had always thought. My personal experience of misinterpreting my own behavior highlights the misunderstandings that society as a whole has about introversion, often by using the term interchangeably with anxiety, though it is clear that the two are very different phenomena within the brain. Overall, introversion technically could be considered as an aspect of psychopathology due to the undefined grey area between personality characteristics and mental disorders. Introversion shares some traits with certain psychopathological conditions, such as an increased likelihood of experiencing anxiety or depression; however, that does not necessarily mean that it is enough for it to be considered a disorder in itself. The distinction between personality and mental illness is still too unclear, as traits like neuroticism, extreme introversion, Machiavellianism, and others can overlap with clinically diagnosed conditions. However, the question of whether it should be classified as a mental disorder is not just a matter of science, but one of perception and societal impact. Labeling introversion as a disorder could potentially do more harm than good; it could reinforce negative stigmas about mental health and perpetuate the idea that introverts need to be “fixed,” rather than simply understood. This is not just a question of whether or not introversion could be considered a mental disorder, but also a question of whether or not it should.

Our current understanding of personality and mental illness is not yet deep enough to make classifications like this, so it is necessary to research personality and psychopathology more deeply, as well as the “grey area” in between in order to understand the boundaries between each. It would be beneficial for research involving personality and psychopathology to be studied together, rather than separately as they have been in the past. By understanding how the two work together, it will be possible to see the minute differences between each sphere, which gives more of a basis to compare what exactly makes the two similar and different. Using only our current understanding, classifying introversion as a mental disorder could lead to unnecessary medicalization of a natural, generally harmless personality trait. The majority of introverts do not experience extreme enough negative symptoms for there to be a need to get serious help or to feel that they need to change. Rather than attempting to pathologize introversion, we should work toward appreciating its unique strengths, such as deep thinking, creativity, and self-awareness. Just as I learned to separate my anxiety from my introverted tendencies, society must also differentiate between introversion and mental illness rather than assume all quiet, introspective individuals are struggling with something that needs to be fixed.

In the future, as we learn more about the causes and structures behind these concepts, our understanding of personality and mental illness will become much clearer and more nuanced. Until then, our knowledge is based on assumptions and incomplete research of the complexity between personality and psychopathology that will one day become understood much more deeply. The end goal should not be to label introversion as a disorder, but to recognize and understand the diverse ways people experience and interact with the world.

APA Dictionary of Psychology. dictionary.apa.org/personality-trait.

Balder, Elizabeth A. “Introversion : Relationship With Mental Well-being.” UNI ScholarWorks, scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/301.

“How to Tell if You’re an Introvert.” WebMD, www.webmd.com/balance/introvert-personality-overview.

“Introversion vs. Social Anxiety.” Mental Health America, mhanational.org/introversion-vs-social-anxiety.

Jylhä, Pekka, et al. “Neuroticism, Introversion, and Major Depressive Disorder-traits, States, or Scars?” Depression and Anxiety, vol. 26, no. 4, Mar. 2009, pp. 325–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20385.

Lai, Han, et al. “Brain Gray Matter Correlates of Extraversion: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis of Voxel‐based Morphometry Studies.” Human Brain Mapping, vol. 40, no. 14, June 2019, pp. 4038–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24684.

Myznikov, Artem, et al. “Dark Triad Personality Traits Are Associated With Decreased Grey Matter Volumes in ‘Social Brain’ Structures.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 14, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1326946.

Ptacek, Radek, et al. “Dopamine D4 Receptor Gene DRD4 and Its Association With Psychiatric Disorders.” Medical Science Monitor, vol. 17, no. 9, Jan. 2011, pp. RA215–20. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.881925.

Reid, Sheldon. “Personality Types, Personality Traits, and Mental Health.” HelpGuide.org, 9 Sept. 2024, www.helpguide.org/mental-health/psychology/personality-types-traits-and-how-it-affects-mental-health.

Results - OpenURL Connection - EBSCO. research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=e2af8b87-8ac2-335e-9c2d-581fefb988bc.

Stein, Dan J., et al. “What Is a Mental Disorder? An Exemplar-focused Approach.” Psychological Medicine, vol. 51, no. 6, Apr. 2021, pp. 894–901. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291721001185.

Torgersen, Svenn. “Personality May Be Psychopathology, and Vice Versa.” World Psychiatry, vol. 10, no. 2, June 2011, pp. 112–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00030.x.

Wawrzonkowski, Mary. “The Introvert Hangover Is Awful.” IntrovertDear.com, 25 June 2021, introvertdear.com/news/the-introvert-hangover-is-awful.

Widiger, Thomas A., and Joshua R. Oltmanns. “Neuroticism Is a Fundamental Domain of Personality With Enormous Public Health Implications.” World Psychiatry, vol. 16, no. 2, May 2017, pp. 144–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20411.

Yang, Junyi, et al. “Regional Gray Matter Volume Mediates the Relationship Between Neuroticism and Depressed Emotion.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 13, Oct. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.993694.

Zou, Liwei, et al. “Relationship Between Extraversion Personality and Gray Matter Volume and Functional Connectivity Density in Healthy Young Adults: An fMRI Study.” Psychiatry Research Neuroimaging, vol. 281, Sept. 2018, pp. 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.08.018.

A huge thank you to everyone who submitted their work, and heartfelt congratulations to those whose pieces were selected for publication! Your brilliance lights up these pages. We can’t wait to see what you’ll bring to the table next month—keep the creativity and curiosity flowing!